Modern instruction-tuned language models, or LLMs, are the latest tool in software engineers’ toolboxes. Joining classics like databases, networking, hypertext, and async web applications, we now have a new enabling technology that seems wickedly powerful, but whose best applications aren’t yet clear.

ChatGPT lets you poke at those possibilities. You can prototype some wild and intriguing experiences in a GPT-4-powered chat window. Experiences that, at times, feel like you’re talking to an AI.

ChatGPT also helps you better understand LLMs’ many weaknesses: their limited math capabilities, their tendency to forget, their struggles to follow many instructions at once, and their proclivity to make shit up.

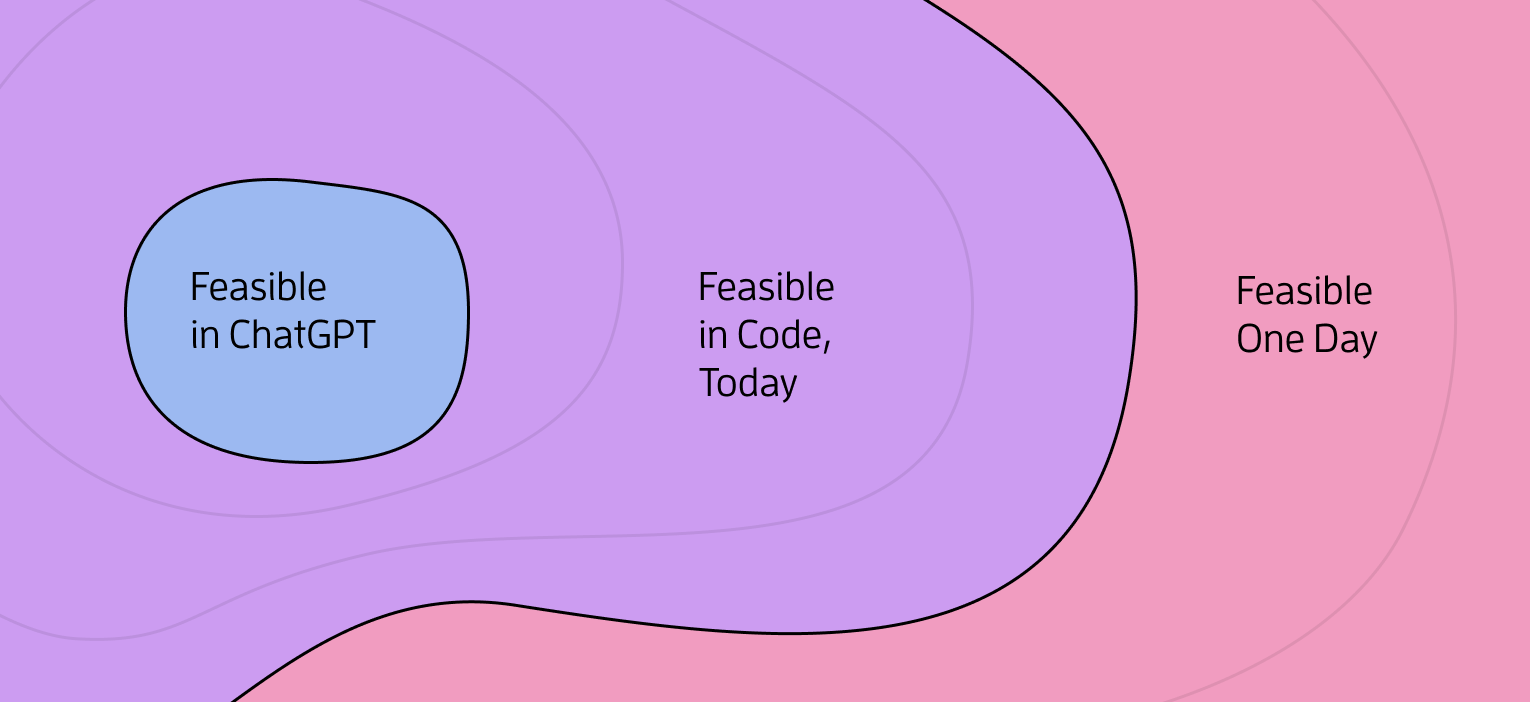

What ChatGPT is not very useful for is understanding how you can compose LLMs with other tools into a polished user-facing product. You know, something you can build a business on. ChatGPT-based prototypes tend to be initially exciting, and then disappoint when you hit the limits of that environment. (Or, alternatively, when it dawns on you that your concept is so simple that your potential customers should just use ChatGPT directly.)

This can mislead people into thinking that exceeding ChatGPT’s capabilities will require some kind of scientific breakthrough.

ChatGPT is a powerful but tiny sandbox.

While current LLMs can’t fully replace human skills for many tasks, they’re already useful for greatly accelerating and levelling up many human efforts. The trick is to compose them together with other tools that mitigate the models’ weaknesses, going beyond a simple chat workflow.

Luckily, this becomes possible with a bit of orchestration glue code. You might build this yourself, or use a burgeoning tool like LangChain or Semantic Kernel. Either way, once you’re interacting with an LLM through a programming environment, you can use a wide array of approaches to break out of ChatGPT’s little box.

Let’s look at just ten of them.

1. Turn the knobs

First off, language models have various generation settings that can lead to quite different results. While most of the parameters will only incrementally improve (or deteriorate) results, there is one powerful capability here: near-determinism.

LLMs have a temperature parameter that, at its default level, will spur more creative and interesting results. However, a temperature setting of 0 will tell the model to consistently generate the most likely output for a given input. Basically, to be boring.

A temperature of zero can be very useful for applications where being correct and consistent is more important than being interesting and engaging.

2. Equip your LLMs with tools

LLMs are good with language, but weak at some tasks that computers are typically good at. Luckily, it’s conceptually straightforward to mitigate this by giving LLMs tools.

For example, it’s become well-known that LLMs aren’t great at math. This might seem like a big limitation, but you can prompt your model to perform math not using language inference, but instead by calling a procedural calculator function that you’ve provided. This is analogous to the way humans would do math: if it’s simple, we might do it in our heads, and perhaps be wrong. If a calculator is handy, we’ll use that.

This generalizes: give the LLM a new tool, and bam! Your language model can do language things, while your procedural code (cheaply) computes things. It can be a match made in heaven.

This approach works for most things you could define an API for. You can give an LLM the tools to call Zapier, invoke shell scripts, search the internet, check the weather, read or write from a database, or call any simple function or query you tell it about. ChatGPT plugins productize this approach, and LangChain has supported tool usage for a while. A couple weeks ago, GPT-3.5 and GPT-4 were update to better understand custom function-calling, so those APIs now have first-class support for telling the LLM about the tools it has available.

Let’s look at one kind of wild case of tool usage.

3. Give your LLM an interpreter

One of the debates going on in the software world is: will LLMs make software development 10% faster, or 10x faster? Folks who lean towards the 10% answer typically haven’t yet had these two experiences:

- Using GPT-4 to help build software that GPT-4 understands well

- Using a workflow that automatically interprets an LLM’s code output

For example, you could have an LLM generate a new class, then procedurally check to see if that class passes your suite of automated tests. If it fails, feed the errors back into the model to try again. This won’t yield 100% autonomous coding, but it can get you a lot further faster than pasting things into ChatGPT will.

More generally, letting an LLM reason using code can be really powerful. It’s fairly well known that you get better answers from LLMs by asking them to “think step by step” and output their chain of thought before their final answer. A level up from that technique is to have it convert the chain of thought into a Python script, which when executed will determine the answer.

Of course, you can get ChatGPT to produce Python and paste it into an interpreter by hand. But in a LangChain-like scripting environment, that code evaluation can be a part of the workflow. This loop can, in turn, be a building block of features and products that we haven’t fully conceived of yet.

(Surgeon General’s Warning: Giving an LLM a code interpreter and access to the internet at the same time should be done only with a healthy dose of paranoia.)

4. Chain your prompts

Chaining is a bread-and-butter technique for building applications on LLMs. While GPT-4 is much better than GPT-3.5 at following multi-part and multi-stage instructions, complex enough prompts will still lead to rules and details getting dropped on the floor. Current LLMs do better with a narrowly scoped task and examples, so developers typically split their multi-part prompts into two or more chained requests.

For example, in a game you might first have the model describe the awesome scene in front of your player with lots of creative gusto, and then have a second prompt studiously generate reasonable multiple-choice options for the player given that scene. Or you might first ask a cheap model if the user’s question is about science, and if it is then ask an expensive science-aware model to consider their question.

A surprisingly useful application of chaining is to have a prompt that evaluates outputs from another prompt. While relying on models to evaluate themselves can certainly get you in trouble if you do it naïvely, in many cases GPT-4 can do useful grading of another prompt’s work, either to initiate a retry, halt, or human-review flag.

You can also use self-grading to get more creative or interesting output, especially when quality matters more than speed or cost. You can ask an LLM “Generate 20 potential headlines for this story”, feed that into “Score each of these headlines given these four criteria”, then programmatically choose the most promising one.

Of course, the LLM’s idea of the most promising headline might still occasionally be janky garbage. More on that later.

5. Let your LLM think in secret

Everything ChatGPT generates is shown to the user. That’s fine for some use cases, but it can undermine certain product goals. For example, if you want an LLM to facilitate a great tutoring session, game, or any other activity where a human would keep notes or collect their thoughts before speaking, you want a model attempting the same task to be able to generate “internal thoughts” before generating something user-visible.

This can be as simple as telling the model that to first output its chain of thought or hidden reasoning wrapped in <hidden>, then follow with its user-facing output. When you render the result, just display the non-hidden text.

Since that can be a bit error-prone, real-world applications typically use prompt chaining to allow for hidden work – intermediate prompts produce interim “thoughts”, which get fed into the prompt that generates the user-visible output.

6. Prompt your model dynamically

Another big limitation of ChatGPT is that the prompts are static text you paste in. To build actual products on this tech, product engineers generally use some kind of templating system to feed their model different variations of a prompt at runtime.

Dynamic prompts often include variables for user context, known-good output examples, knowledge base articles, documentation, and more – all sized to fit within the relevant context window and cost constraints in production.

Templating as a prompt engineering tool is obvious, but is a good illustration of why getting out of ChatGPT and into code unlocks some pretty fundamental experimentation and iteration tools.

7. Provide the facts

Facts are the most common things engineers put into their prompt templates. LLMs famously tend to confabulate factual information that seems plausible when they’re not sure. Tamping this down at the model level is a fascinating area of active research, but today we can help a lot by adding relevant true facts to our inputs.

For example, to respond to a user input, e.g. “How is Slurm made?”, you might first query a vector database populated with embeddings. This lets you pull out facts that are semantically similar to the user input. Feeding in those vetted Slurm facts along with the user’s question can dramatically reduce the model’s reliance on its pre-training, which may have been disastrously light on Slurm-related insights.

In this way, we can often use LLMs to get good output for topics that are either obscure, newer than the model’s data cutoff date, specific to your product, or just underrepresented in the existing data sets your model trained on.

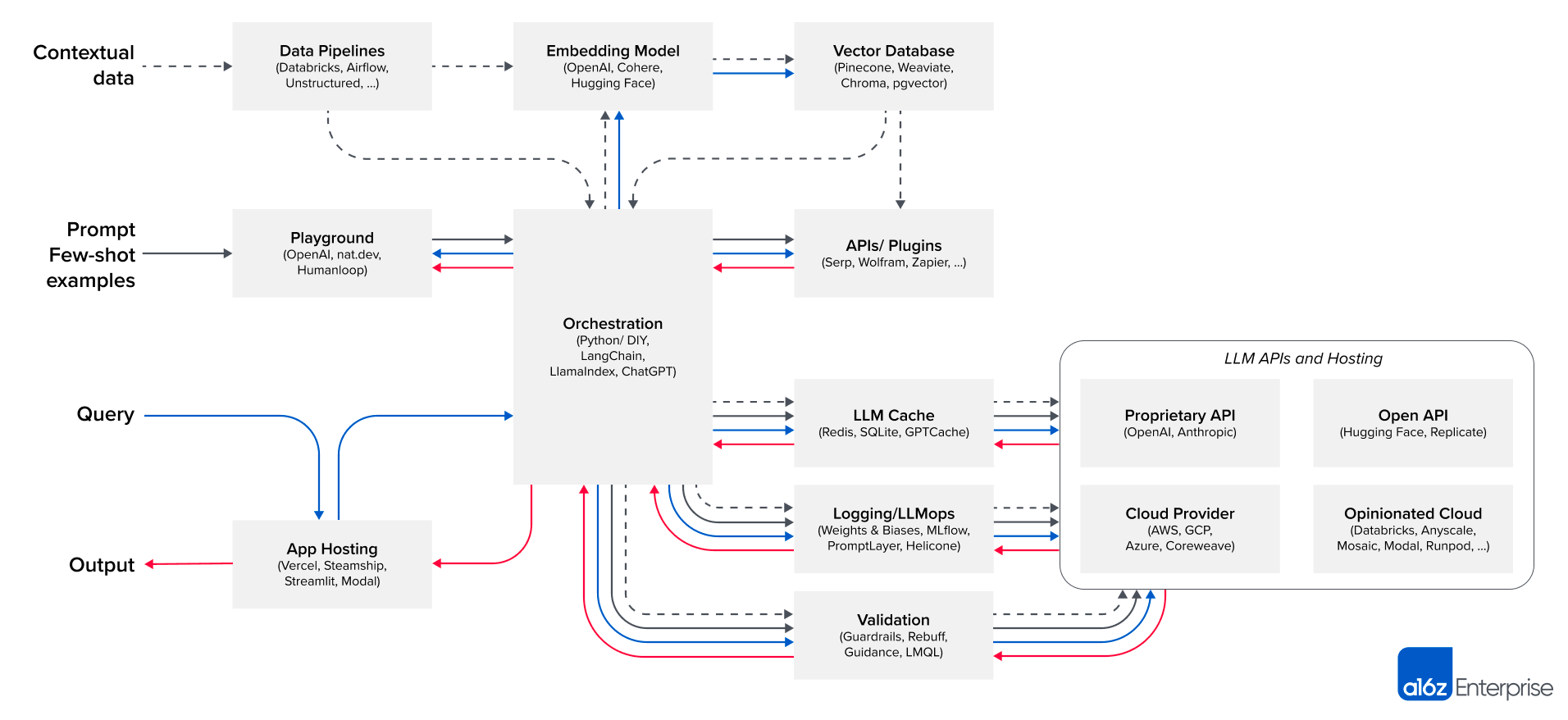

If my guide isn't enterprisey enough for you, A16Z has this architecture diagram for LLMOps with a handy list of products they've invested in you can use.

A special case of providing the model with facts is establishing a “memory”. ChatGPT does one specific kind of this: it sends the most recent few thousand words of text in your chat thread to the model when you make a new query. In that way, ChatGPT has some short-term memory.

Back in the ancient times – four months ago – I speculated that large context windows were necessary to one day create an LLM-powered agent that feels like it has a stable and growing memory over the long term. Between Anthropic’s new 100k-token context windows and procedural tools for letting models store and retrieve key facts, it’s now completely possible to build a companion or coach that behaves as if it has a long-term memory.

Hold on to your butts.

8. Build non-chat-like experiences

While chat experiences are going to be massive and keep getting more useful, chat is just one thing we can build with LLMs. Product designers’ imaginations are just starting to scratch the surface of what is possible here.

Talented designer Maggie Appleton has a great exploration of these UX possibilities titled “Why I Hate Chatbots”. The core idea is that language models can help us analyze, remind, suggest, categorize, challenge, label, automate, and otherwise power quality-of-life features that have nothing to do with chat or even composing text.

If you find your team stuck wondering, “What text fields in our product could we have an LLM generate text into?” then challenge yourself to get outside of that box.

9. Swap out your model

As of June 2023, most product teams building on LLMs are using OpenAI’s GPT APIs. (That is, if they are permitted to by their corporate legal and compliance overlords. Otherwise, they’re probably struggling to get something comparable out of current open-source alternatives.)

Once the available models and our LLMOps skills mature, this will shift. There are thousands – tens of thousands? – of teams experimenting today with fine-tuning open-source models to get good-enough performance on specific tasks. Tuned smaller models can, in theory, avoid the cost, compliance, or legal concerns around OpenAI’s GPT APIs. While fine-tuning was once an expensive dark art, Parameter-Efficient Fine Tuning methods such as LoRA are making this more cost-effective, and tools are inbound that will make fine-tuning more user-friendly.

Today, fine-tuning isn’t currently supported on OpenAI’s GPT APIs. Reportedly though, this is just because they can’t yet buy GPUs fast enough to meet demand. By 2024 it seems likely that LLM-fuelled products will often use different fine-tuned models for parts of their prompts – or categories of input query – that today have been prototyped as one large generic ChatGPT prompt.

Going even further, LLMs are great for prototyping and discovering use cases for ML, but “Traditional” ML techniques are capable of some of the same things. Once you’ve proved a concept with an LLM and are looking to scale it up in production, it can be worth reconsidering if LLMs are even the best way to scale and iterate that feature, and whether more traditional machine learning approaches could get you the same result faster and cheaper.

10. Put a human in the loop

While LLMs will change knowledge work in profound ways, they are still essentially accelerators for human endeavours. In a lot of cases, ChatGPT-based product prototypes stumble because they’re prompted to exclude the human element, and leap right to a final answer unassisted.

Part of the reason that Github Copilot, and the hotly anticipated GPT-4-powered Copilot X, are breakout killer apps for LLMs is that they’re fundamentally human accelerators. GPT can’t even remotely build and maintain large software applications on its own, but Copilot is an excellent coding buddy – an amplifier of your existing skills and intentions. By making suggestions and taking a first pass at less-creative parts of the work, Copilot makes its human pilot more effective.

There are many cases like this. Today’s LLMs struggle with fully-automated workflows, but can often generate compelling options or starting points for humans to jump off from.

When prototyping and exploring LLM-powered products, I encourage you to explore not only how we can automate, but how to accelerate and empower people. Modern machine learning models can help us learn, discover, and achieve more than we could before.

I’m excited to see what you all build with it.

And a little terrified. But mostly excited.

Thank you to the many folks I’ve interviewed recently to develop my understanding of how LLMs are being applied today, especially Rahul Behal, Matt Deakos, Shawn Jansepar, Jonathan Kressaty, David Hariri, Ron Harlev, Boris Lau, Bonnie Li, Dennis Pilarinos, Tavis Rudd, and Peter Werry. Also big thank you to Simon Willison, whose writing about his learning has helped accelerate my learning about this wild world.